At dawn in early October, in Itasin, Ogun State, Neye Afolabi set out for his farm, just a short walk from his home. But before he could begin tending his crops, a herd of elephants emerged from the forest and trampled through his farmland.

“I could not work on my farm this morning because of elephants,” he said. “I ran away and was watching them from afar. I waited for about an hour, hoping that they would leave so I could do my day’s work. They did not leave. Instead, they were busy destroying it and eating my crops.”

Many residents of Itasin, a rural community in Ijebu East Local Government Area of Ogun State, have either had their farms destroyed, been physically attacked, or narrowly escaped encounters with elephants that wander in from the nearby forest reserve. The conflict is largely driven by illegal farming and commercial logging inside the reserve, which has pushed some elephants into surrounding communities and disrupted the habitat for those that remain.

Established in 1925, Omo Forest became Nigeria’s first United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Biosphere Reserve in 1977. It is a rainforest home to rare and endangered species, including an estimated 100 African forest elephants, white-throated guenons, 125 bird species, and more than 200 tree species, along with various butterfly populations. Satellite data from the University of Maryland shows that the forest lost more than 7 per cent of its tree cover between 2001 and 2018.

Two signposts indicating hunting, grazing, farming and logging are illegal in the elephant zone. Photo Credit: Sodeeq Atanda.

On July 28, Yaya Musa Kalamu, a resident of the area, was killed by an elephant while felling trees for commercial purposes inside the forest.

Conservation workers recall that on May 13, 2018, a group of 15 elephants migrated from the Omo Forest Reserve to the Itasin community. The movement, they say, was driven by continuous illegal logging and farming-related deforestation within the reserve, a period that coincided with documented tree-cover fragmentation.

“That year, the loggers invaded the core of the elephant zone, and they were forced to migrate,” said Emmanuel Olabode, project manager for the Elephant Initiative, a project of the Nigeria Conservation Foundation (NCF) in partnership with the Ogun State government.

Onyebu Titus, the chief forest guard who has worked with the NCF for 35 years, told Dataphyte that he tracked the migrating elephants until they crossed the Lagos-Ore Expressway.

Forest guards clearing the pathway to their base camp on October 2. Photo Credit: Sodeeq Atanda.

“They caused a momentary traffic jam on both sides of the expressway. Travellers could not believe their eyes that elephants could be seen around here,” Mr Titus said.

These elephants found a home in the Itasin community forest and were gentle-natured. They would casually walk into the community, eating plantains and backyard farm crops.

FARMING AND LOGGING IN OMO FOREST

With a size of 130,600 hectares, the Omo Forest serves a dual mandate: it is licensed for commercial logging and elephant conservation. But there are no clearly defined boundaries, putting the elephant zone at risk of invasion and illegal activities.

“We have a proposed size for the reserve, but I can’t disclose it yet because the government has not approved it,” he said. “Once it is approved, enforcement will be easier, and our relationship with the villagers will improve. They will clearly know which areas are strictly off-limits for farming and logging. Without a documented boundary, enforcing protection is very difficult.”

A faulty lorry loaded with wood on a slippery road inside the Omo Forest Reserve. Photo Credit: Sodeeq Atanda.

In response to Dataphyte’s request for comment, Ogun State Commissioner for Forestry, Taiwo Oludotun, said the state remains committed to conservation, which he suggests is focused on the 50 thousand hectares-large conservation zone.

“The area in question is known to all stakeholders (Farmers, Baales and all community members) as a no logging, no farming and no hunting zone,” said Commissioner Oludotun. “Such activities are illegal, and the government has always frowned on anyone who perpetrates such illegal activities in the forest reserve.”

Acknowledging the challenges of enforcement, he added, “Many illegal farms and structures have been demolished, and offenders have been prosecuted and convicted. We have repeatedly issued public notices in newspapers and on the radio advising illegal farmers and settlers to vacate the conservation area. Cocoa farming is strictly prohibited in our forest reserves.”

A cocoa plantation inside the protected zone. Photo Credit: Sodeeq Atanda.

In the hard-to-reach parts of the forest, several settlements, motivated purely by cocoa farming fortunes, have sprung up. Even with government-erected signposts reading “No hunting, grazing, farming, logging,” farmers comfortably carry out their trade with the knowledge of the same government.

Dataphyte learnt that each farmer has an identity card recognised by the Ministry of Forestry. These farmers come from different states to farm in the forest. By December of each year, they would hire security guards to secure their settlements and travel back to their various states and return on January 23 to continue their business. There were also allegations of farmers paying huge sums to some government officials to lease portions of the forest for cocoa farming.

When asked for comment, the forestry commissioner confirmed it, saying it was not a license for farming but for security reasons. He added that no reports of official bribery had been reported to him. “The identity cards with the residents of Omo Forest reserve did not legalise farming and logging in the conservation area, but rather to enable the ministry to have a database of those residing in the forest reserve so that criminal elements or bandits do not hide in the forest to perpetrate criminal acts,” said Mr Oludotun.

“I am not aware of any official who received a bribe from farmers to lease land in Omo Forest Reserve. The fellow conducting this exercise may wish to present those individuals who have received or taken bribes from farmers for land leasing.”

While in the forest, Dataphyte observed that numerous footpaths connected to countless farmlands, starting from Omo Bridge 2, a settlement led by Ajayi Adeshina, the Baale of the settlement.

Many of the farms were located far from immediate sight as they were in the middle of forest trees. In some cases, Dataphyte saw cocoa and plantain farms located within the elephant sanctuary.

“Each farmer has an ID card known to the government. We admit this is an elephant forest and we are the ones invading their house,” Muniru Akinleye, a farmer and Oluode of Eseke, told Dataphyte.

“They [elephants] frequently eat and destroy our crops. For me, I no longer have maize and yams; elephants have consumed them. Even on my cocoa farm, they come there and eat it. But I know some will be spared, and I will harvest them at the end of the day. I saw an elephant on my farm recently, and I quickly jumped on my motorcycle and returned to the village. So, yes, they feed on our farms.

“But we cannot really do anything. We cannot complain to the authorities. Elephants are government property; we are citizens. If we complain, the government will take the elephants’ side, and they might order our evacuation. For this not to happen, our coping mechanism is silence and managing what is left of our farms to sustain our families.”

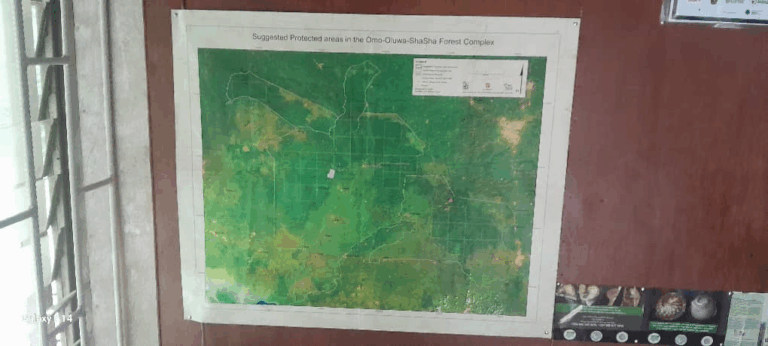

An old map of the forest. Photo Credit: Sodeeq Atanda.

What is considered the elephant zone is a very tiny portion of the forest, and it is situated somewhere in the extreme side of the forest, according to an old map sighted by Dataphyte. The entire forest straddles two local government areas: the Ijebu East Local Government Area on the front, starting from the Lagos-Ore Expressway, and goes beyond the region called J4 (supposedly meaning Jungle 4); and then the Ijebu North Local Government Area, which begins shortly after the elephant zone.

So those local council areas serve as two areas of operations for two groups of loggers. According to NCF officials, those in the Ijebu East area do not really operate close to the zone, but those in the Ijebu North. Given that elephants walk and play around, the sounds of chainsaws and other logging-associated disturbances could disturb elephants without discrimination.

In an interview on October 1, Modinat Alaga, whose mother, Mulikatu Rasheed Alaga, is a logger in Akorede Camp, denied that loggers routinely invaded the protected zone.

Modinat Alaga. Photo Credit: Sodeeq Atanda.

“For instance, my mother has her own government-allocated logging arena, and she doesn’t go beyond it. She only operates in places allocated to her, and she has a valid license. She has a “propatin”, a sort of hammer used to mark her wood, and government guards will also mark them too,” Modinat Alaga told Dataphyte.

“Yearly, we pay N5,000 or more to renew the license with the government. The government doesn’t allocate the elephant zone to any logger, and nobody dares go there. There is the government zone, and there is the elephant zone. My mother could operate here [around the village, which is a stone’s throw from the elephant zone] because it’s within the permissible logging area. For our farms, we don’t budge when elephants destroy them,” Ms Alaga explained.

Ms Alaga added that loggers pay the government for reforestation. While touring the conservation forest, Dataphyte observed a few small portions of land where young teak trees were growing. According to the chief ranger, the communities were responsible for them.

The NCF also regularly regrows trees where necessary. Project manager Olabode said, “In our nursery plantation, we have over 20,000 seedlings waiting to be replanted. We do this regularly because reforestation is a continuous agenda for us.”

ITASIN COMMUNITY’S NIGHTMARE

The displaced elephants were resettled in Itasin, a rural conclave on the northern side of the Sagamu–Benin Expressway and situated about 10 kilometres away from the Omo Forest. In the early days of their arrival, residents said that the elephants were moving freely in the community, looking for food, and would return to the forest.

A signpost of a public primary school in Itasin Community. Photo Credit: Sodeeq Atanda.

“Their sight was adventurous to us,” said Sanwo Odugbemi, an elderly resident of the community.

“We did feel threatened by their presence. They would eat plantains, pawpaw and crops within sight. They are the reason why you cannot see pawpaw anywhere in our neighbourhoods again.”

According to Sanariu Abimbola, an indigene of Itasin, Oba Felix Adegbesan, the immediate-past Onitasin of Itasin, protected the forest and ensured that trees were only cut down once in a while when someone needed them for a personal housing project or the community needed them for a collective project.

Logging was not a practice. But Dataphyte learnt that after the death of Oba Adegbesan in June 2024, residents and their alien partners began logging at a commercial scale.

This logging began threatening the elephant habitat, and hostility between the wildlife and community members started to grow.

“I can confirm that commercial logging occurs in the forest, and it could be contributing to elephants’ hostile behaviour,” Mr Odugbemi said. “The government has asked that we report any logging activity to them. But in truth, what will the loggers be living on if the government bans their trade here?”

Following the attack on Musa Kalamu, reports described him as a farmer. But Dataphyte’s findings confirmed he was a logger and was on duty when the elephants killed him.

Mr Afolabi, the young man earlier mentioned, said he was the one whom Akorede Yaya, the deceased’s son, ran into after the attack.

“The news swiftly spread, and we mobilised to the scene. On getting there, we saw that the elephants were more than one, and they refused to leave,” Mr Afolabi recounted. “We could not move closer to them. The attacking one angrily used its tusk to fling the man away. He was still alive, but his internal organs had been disembowelled. He died on the way to the hospital because we could not get a vehicle to carry him on time, and the hospital is far.”

When asked why the media narrative described the deceased victim as a farmer rather than a logger, Mr Abimbola said, “It may be the residents’ tactics of shaping their information flow to ensure that the true nature of the activities in the forest is concealed.”

Mr Odugbemi and four other residents present when Dataphyte was interviewing them collectively said they wanted the government to “come and capture and return the elephants to Omo Forest because their presence in our community benefits no one”.

But for Mr Abimbola, “The elephants could bring positive attention to our community and put it on the global map. So, rather than return them, we should start planting other crops, such as pepper, that they cannot eat. That way, we can co-exist with them peacefully.”

In his response, Commissioner Oludotun said there was no plan of relocating or airlifting the elephants from Itasin forest, and “that is why the landscape management approach was adopted. This is because when forest elephants are airlifted, unlike savanna elephants, they do develop complications due to stress and die, thus wasting the resources incurred in the air lifting exercise”.

In response to Musa Kalamu’s killing, the commissioner said that the community forest was a designated wildlife conservation area, especially for elephants.

Itasin residents rejected Commissioner Oludotun’s statement that the forest was a conservation zone. While in the community, Dataphyte saw nothing to confirm the official designation claim. Unlike the Omo Forest, the Itasin forest had no forest guards, no signposts, or any other distinguishing markings to suggest it had been converted to a forest reserve.

Responding to a question on this matter, the commissioner informed Dataphyte that Governor Dapo Abiodun had approved the designation of the forest as a protected wildlife sanctuary in April 2023, and a gazette was being prepared to this effect.

“The Bureau of Land in the state has produced a provisional map of the area, and efforts are ongoing to publish the gazette in this regard. As a follow-up to this, the ministry has engaged conservation non-governmental organisations to work with community members in the area for sensitisation and enlightenment, along with government officials to prevent human and elephant conflict,” said the commissioner.

“In one of our engagements with community members, they were made to see the provisional map of the wildlife sanctuary, and this abated their fears, and they were assured of the government’s commitment to the process, and they were quite happy with the process.”

This story was produced as part of Dataphyte Foundation’s Biodiversity Media Initiative project, with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.