An international team of scientists has now analyzed more than 200 scientific studies on 73 animal species in a meta-study to determine exactly how climate change is related to phenology, morphology and population trends.

The team explains in an article published in the journal Nature Communications that phenological traits—seasonal developmental phenomena—are very sensitive to temperature changes and that this represents a mechanism for many species to cope with climate change.

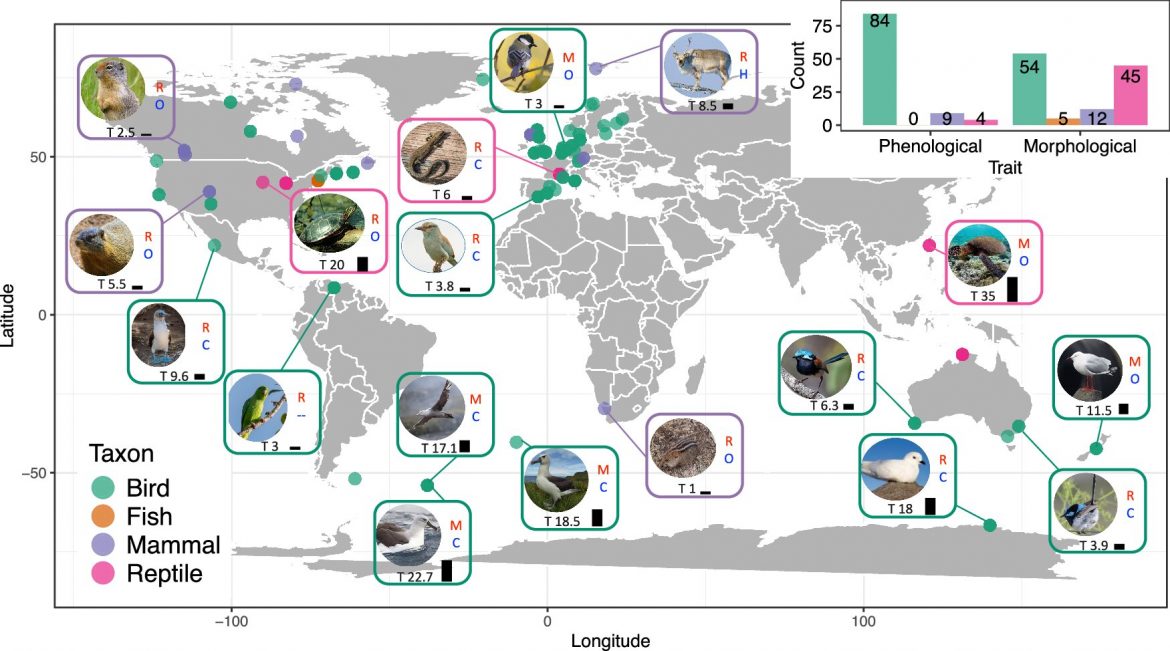

Different kinds of adaptations can help animals cope with climate change and maintain stable populations: These can confer changes in behavior, physiology or body size. An international team of scientists from more than 60 research institutions led by the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW), James Cook University and University College Cork analyzed 213 scientific studies for links between climate change and phenology (e.g., start of breeding or return to summer quarters), morphology (e.g., body size, weight or shape) and population development of a total of 73 vertebrate species.

The team looked not only for evidence of the influence of climate change on specific fitness parameters of animals—such as survival rate or reproductive success—but also on the changes in population numbers of those species. Most studies examined birds (65%), followed by reptiles (23%) and mammals (10%).

Read also: NASA reports record heat but omits reference to climate change

An important criterion for the selection of studies was the availability of long-term data sets on phenological or morphological variables and population size, to be able to confidently reveal the patterns. Typically, the studies used data from 15 to 25 year periods.

From the relevant phenology studies (97 studies), the scientists were able to deduce clear evidence that seasonally recurring developmental processes are significantly influenced by changes in temperature. In warmer years, they observed a shift in breeding times and other phenological characteristics mostly toward earlier dates, but in some cases they also observed a delay in the processes.

“We were able to show that shifts in seasonal developmental events allow populations to remain stable or even increase in their numbers,” says Dr. Viktoriia Radchuk from the Leibniz-IZW, lead author of the meta-study published in Nature Communications.

“The majority of studies also showed that temperature-induced shifts in phenology are adaptive responses. This means that the adaptations are effective coping mechanisms for dealing with climate change, for example, by shifting the actual timing of egg laying in a bird species to coincide with the shift in the optimal timing for egg laying.”

However, the meta-study also pointed toward maladaptation to climate change in a notable number of cases. “The effect of warming on phenology is very clear, but the implications for wildlife are heterogeneous,” says Dr. Tom Reed from University College Cork, a shared senior author of the study. “We are probably dealing primarily with so-called trait plasticity and, in the periods studied, not yet with evolutionary processes. Phenological traits can obviously be adapted flexibly enough by animals.”

Story was adapted from Phys.org.