As a boy in the 1970s, Mathew Osaronwaji often led groups of children down to Nsisioken, a cool, winding stream that flowed through Agbi Ogale, a community in Nigeria’s oil-rich Rivers State. At 15, he was already skilled with nets and hooks, catching shrimps, catfish, bonga shad, tilapia, and even electric fish.

“The harvest was always bountiful,” he recalled. “It was a source of protein and a means of livelihood for our families.”

Back then, the waters of Ogale, part of Ogoniland, teemed with life. The community hosted a yearly fishing festival where children from neighbouring villages competed to fill their baskets first. Then, it wasn’t unusual for a single family to haul in 100 kilograms of fish in a day. Those who didn’t have boats stood by the water’s edge, casting their hooks and lines.

In addition to the Nsisioken Stream, the Ogale community had seven other streams, namely Nmu Okulu Ogale, Oken Mba, Oken Adaran, Okulu Ebo, Oken Eta, Nmu Okon, and Nmu Chapun. These streams were not just rich fishing grounds but also vital sources of drinking and cooking water for the community.

Mathew Osaronwaji stands close to what is left of the Nsisioken stream

Mathew Osaronwaji stands close to what is left of the Nsisioken stream

Today, those memories feel like they belong to another lifetime. Since the late 1980s, repeated oil spills have devastated Ogale’s natural environment, eroding its once-rich biodiversity and natural capital.

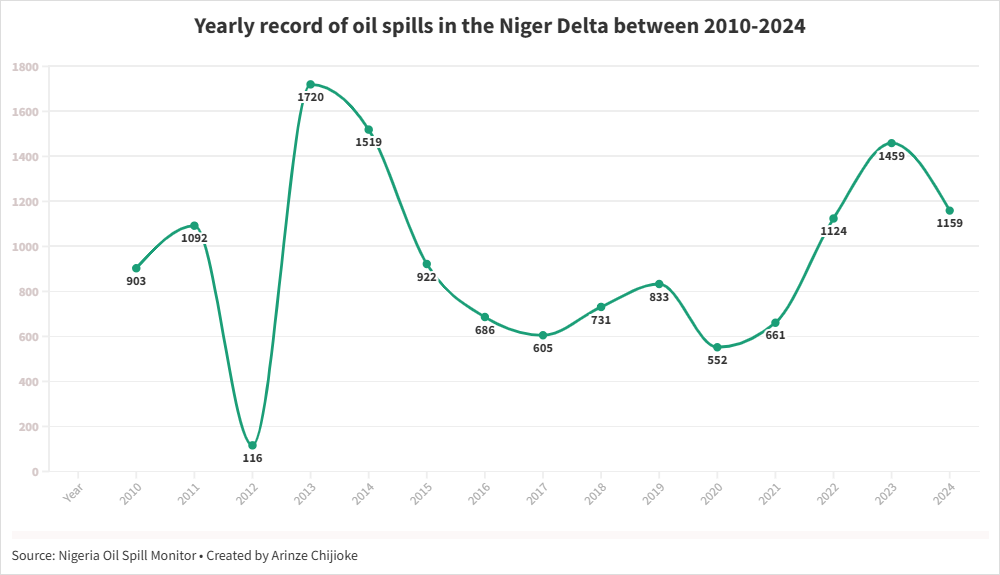

Decades of oil exploration and production activities by oil companies have turned Ogoniland into one of the “most polluted” places in the world. According to the United Nations, at least 1.5 million tons of crude oil have been spilled across the Niger Delta since 1958 in more than 7,000 incidents, with Ogoniland, comprising 261 communities spread over nearly 1,000 sq km (385 square miles), being the epicentre. Between 1976 and 1991, more than two million barrels of oil polluted Ogoniland alone in 2,976 separate oil spills.

Shell, one of the main operators in the region, has left a long trail of pollution in Ogale, a community of about 40,000 people. Records show more than 40 oil spills linked to its pipelines and infrastructure since 1989. The company’s own data indicates that, on average, more than two spills have occurred every year, including at least 55 spills in Ogale since September 2011. Although Shell suspended operations in Ogoniland in 1993 following widespread protests over environmental degradation, the legacy of contamination continues to shape daily life in the community.

Now, as Shell withdraws from onshore operations in the challenging Niger Delta terrain, its assets – and their legacy of contamination – are being handed over to a Nigerian consortium, Renaissance Africa.

Biodiversity on the brink

More than two decades after Shell ceased drilling, Ogale’s streams remain contaminated, and its once-thriving fish population has all but vanished. “Our fish have gone into extinction,” said Mr Osaronwaji, now president of the Agbi Improvement Union. “Back then, it was common to see porcupines, grasscutters, and other animals near the streams. Now, they’re gone.”

An environmental scientist at the University of Port Harcourt, Dr Lebari Sibe, said that oil spills kill fish directly, destroy their habitats, and hinder natural recovery, which can eventually lead to the local extinction of certain species.

“When crude oil spills into rivers, creeks, and mangroves, he said, it coats the surface of the water, blocking sunlight and reducing oxygen exchange, which suffocates fish and other aquatic life,” explains Dr Sibe. “Toxic components of the oil, such as benzene and heavy metals, contaminate the water and sediments, poisoning fish directly and impairing their ability to reproduce.”

Contaminated stream in the Ogale community

Contaminated stream in the Ogale community

He added that over time, these pollutants also kill plankton and invertebrates, disrupting the food chain. In places like Ogale, where spills remain unremediated for decades, habitats are permanently degraded, making recovery nearly impossible.

“If the ecosystem remains unfavourable or conducive for their survival, they will not appear,” he noted.

A recent visit to the Ogale community revealed crude oil still floating on two of its streams, with the stench of petroleum thick in the air. Nsisioken, once the pride of the community, is now partly a waste dump, its banks overgrown with weeds.

Memories of a once thriving Past

Eunice Osaronwaji married into the Agbi Ogale community in 1980. She still longs for the days when fishing sustained families and life revolved around the streams.

“Apart from fishing, families planted vegetables, peppers, and water yams around the swampy areas,” she recalled. “The harvests were always bountiful. Today, we can no longer farm near Nsisioken Stream,”.

Eunice Osaronwaji misses the days of farming vegetables around the stream

Eunice Osaronwaji misses the days of farming vegetables around the stream

Friday Oyor, another elder in the Ogale community, remembers when the Nsisioken Stream was surrounded by lush mangrove ecosystems that served as nurseries, feeding grounds, and habitats for fish, crustaceans, birds, reptiles, and mammals.

“We had palm trees and other species such as Acacia, locally known as Ngorongo, growing around Nsisioken,” Mr Oyor said. “They provided habitats, food, and shelter for birds, mammals, and insects. Now, they are all gone, our swamps, our fishing nets, everything.”

With their streams now contaminated, Mr Oyor and other residents of Ogale are forced to buy fish at exorbitant prices from Nchia General Market or Eleme Market. They even purchase drinking water from vendors.

Friday Oyor says the stream was surrounded by lush mangrove ecosystems

Friday Oyor says the stream was surrounded by lush mangrove ecosystems

For environmental activist Solomon Oyor, the oil spills have destroyed more than livelihoods; they have also eroded cultural traditions. He laments the loss of Oken Adaran, a revered stream where young women once performed pre-marriage water-fetching rituals.

“What worries me most,” Mr Solomon Oyor said, “is that I don’t believe the remediation agency will restore the Ogale community to what it used to be, not with the pace and quality of work being done.”

His concern reflects findings from U.N. documents obtained by the AP News, which revealed that the cleanup of Ogoniland, including Ogale, as recommended by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), has been largely mismanaged.

Solomon Oyor says cultural traditions have also been eroded by oil spills

Solomon Oyor says cultural traditions have also been eroded by oil spills

No cleanup for Nsisioken

In its 2011 report, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) found that water from Nsisioken was contaminated with benzene, a known carcinogen, at levels over 900 times above the World Health Organisation (WHO) guideline. UNEP recommended that the contamination required emergency action, prioritising it above all other remediation efforts.

However, findings show that no remediation attempt has been carried out in the area.

“We don’t know why HYPREP has not come here, since the reports say it should be addressed first; they have not visited, carried out any assessment,”. “We feel abandoned by the government and Hyprep, and we cannot go back to fishing,” said Mr Osaronwaji.

Although soil and groundwater remediation is ongoing in parts of the Ogale community, many residents doubt its effectiveness, pointing out that underground water remains contaminated.

Former Community Development Committee (CDC) chairman of Ogale community, Fred Oyor, said that it has been over two years since HYPREP last visited Ogale community, yet groundwater in some locations remains contaminated.

Fred Oyor says groundwater remains contaminated despite HYPREP’s intervention

Fred Oyor says groundwater remains contaminated despite HYPREP’s intervention

“It is even worse than it was before they started their operations,” he claimed. “And nobody is even talking about the Nsisioken River.”

According to Olube Obe, who works in HYPREP’s Public Health Department, Nsisioken River was classified as a complex site, which explains why remediation has not yet started. “We had to begin with the semi-complex sites so that whatever lessons we learn can be applied to the complex ones,” Mr Obe explained. “Contracts are now being awarded for the environmental assessment of those complex sites.”

He dismissed claims that HYPREP’s work has been ineffective, noting that in some locations, contractors dug as deep as 11 metres before discovering that pollution was still present. The site has since been classified as complex and will need to be re-awarded for further remediation.

“Funding remains a major challenge because the level of pollution we have encountered is far beyond what we initially anticipated,” he said, adding that fluctuations in the prices of materials are also affecting the progress of the project.

Move to restart drilling and the pushbacks

Despite unresolved environmental damage, Nigeria’s federal government is seeking to restart oil drilling in Ogoniland. In January 2025, President Bola Tinubu met with Ogoni leaders, urging them to put aside past grievances in the interest of peace and development.

The proposal, however, sparked swift opposition. More than 20 civil society groups rejected the plan, warning that resuming oil extraction would deepen pollution and endanger the health and rights of the Ogoni people.

Crude oil visible on farmlands in Ogale

Crude oil visible on farmlands in Ogale

“The contemplated resumption of oil operations in Ogoniland poses a significant threat to the fundamental human rights of the Ogoni people to a clean and healthy environment, the right to health, and the right to life,” said the coalition. “The resumption of oil activities in Ogoniland is not only a betrayal of the Ogoni struggle but also a threat to the environment and future generations.”

Protest held after planned resumption of drilling was announced

Protest held after planned resumption of drilling was announced

Those fears are not without basis. Just a month after the president’s announcement, a new spill occurred at Shell’s Ogale facility following a valve failure, sparking renewed protests. Residents marched through the community carrying placards demanding reparations and environmental justice.

In June, a landmark ruling by the High Court in London allowed Ogale residents to hold Shell liable for years of pollution, a rare legal victory after a decade-long legal battle.

Back in the Ogale community, environmental activist Solomon Oyor insists that cleanup and restoration must come before any discussion of drilling. “We have been dragged years backwards,” he said. “Beyond remediation, we must restore the native species and revive our environment. Without that, there is no future here.”

“This story was produced as part of Dataphyte Foundation’s Biodiversity Media Initiative project, with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.”